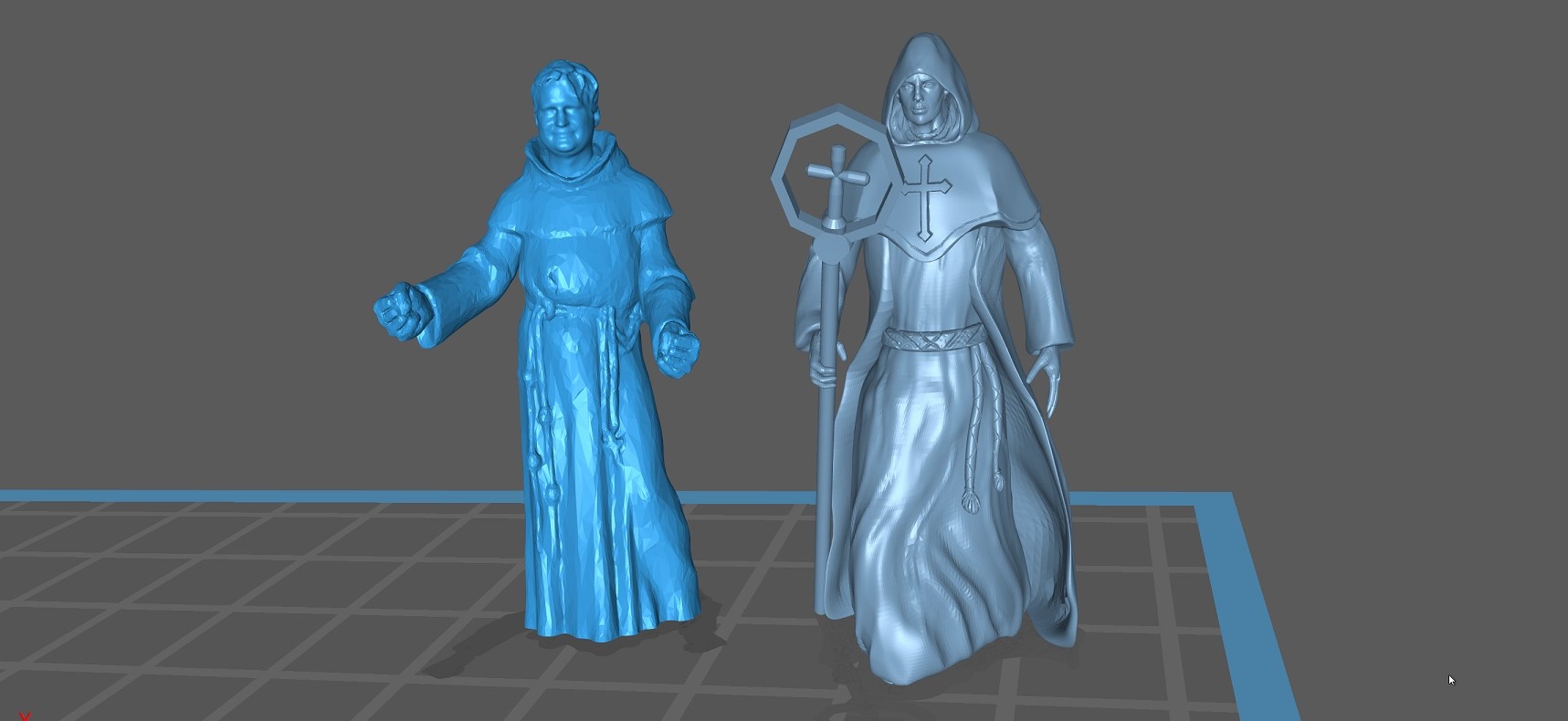

Using three-dimensional digital rendering, Virtual Plasencia explores three formative moments in the life of Gonzalo García de Carvajal offering viewers an inviting and useful learning experience.

In the early 15th century, the Carvajal family began a transformation from serving as lower noble knights (caballeros) to a new generation of church leaders. The first among them to make this fateful transition was Gonzalo García de Carvajal.

With his appointment as archdeacon, Gonzalo García de Carvajal initiated the Carvajal family’s first significant identity transition. Generations of Carvajal men had served as knightsin the king’s armies, although none had ever pursued a churchman’s livelihood.[i] For several hundred years, the Carvajal clan had labored, like the Mendoza family, as “military entrepreneurs.”[ii] However, only those soldiers with personal wealth, proven military talent, and the desire for financial and social advancement could readily enter the upper echelon of Castile’s nobility.[iii] Unfortunately, the Carvajal lacked significant wealth and could boast of only modest successes on the battlefield, in contrast to others like the Estúñiga who owned great armies.[iv] Further, like all noble families, its social and economic status was always in jeopardy. A noble clan could rapidly decline in status if the family’s size exceeded the economic capacity of its resources or if it failed to generate sufficient male heirs to perpetuate the clan’s lineage.[v]

Sometime after the Plasencia knights’ tax revolts of 1396 and 1403–10, the Carvajal family guided Gonzalo García de Carvajal toward ecclesiastical service. This decision forever redirected the trajectory of the Carvajal of Plasencia and began the family’s religious, social, and economic metamorphosis as it adapted to their relationship with the Santa María ecclesiastics. With these early initiatives in place by the first decade of the 1400s, the Carvajal clan was at the forefront of identity change among Castile’s knight clans; other noble families such as the Mendoza delayed their entry into the ecclesiastical world for another fifty years.[vi]

What remains frustrating is our limited knowledge about the family’s and Gonzalo García de Carvajal’s decision to enter ecclesiastical service, as no other Old Christian Carvajal, or extended family member, had served the church. His father, Alvar García de Bejarano was a knight, and his brother, Diego García de Bejarano, had been excommunicated for his role in a recent tax revolt. His mother, Mencía González de Carvajal, was the daughter of a knight.

The one clue that may point to why Gonzalo García de Carvajal was guided toward the church was that his father was more than a knight; his full name and titles were Alvar García de Bejarano “el Rico” and Señor de Orellana de la Sierra.[vii] In fact, in appears that Gonzalo García de Carvajal’s father was a minor and previously undocumented member of the new nobility. There is virtually nothing known about his origins, but the nickname “the Rich” and his ownership of seigniorial lands signals that he was likely among the generation of New Noble houses created by the mercedes enriqueñas, and possibly a first-generation converso. Further investigation reveals that this single family within the extended Old Christian house of Carvajal was the first to become religious leaders. As I explore in subsequent chapters, Gonzalo García de Carvajal had other siblings that departed from the long-standing knightly profession of the extended family. This included Dr. Garci López de Carvajal, who would become a royal bureaucrat, and Sancho de Carvajal, future archdeacon of Plasencia.[viii] As a group, these siblings were initially an anomaly, but soon they would be joined by their maternal first cousins.

The family decisions that led these men to join the church evade us, but what is clear is that the clan had prioritized this immediate family unit as responsible for developing highly educated leaders, men who could bridge the relationships between Old Christian knights and the converso Santa María churchmen who were their extended relatives. This was a shift in religious and professional identities to a new path working alongside first-generation conversos and trading swords for wax seals.

[i] RAH, Colección Salazar y Castro, C–20, fols. 197–217. This statement is based on my review of sources in the RAH, AHHSN, and ACP.

[ii] Nader, Mendoza Family in the Spanish Renaissance, 40.

[iii] Herlihy, “Three Patterns of Social Mobility,” 639–41.

[iv] See chapters 1 and 2 for a discussion of the Carvajals’ caballero origins, lower noble status, and modest wealth.

[v] Herlihy, “Three Patterns of Social Mobility,” 632–33.

[vi] The Mendoza family did not aggressively advance into the church service until King Juan II’s 1458 appointment of Pedro González de Mendoza as bishop of Calahorra. Even though the Mendozas recognized the importance of ecclesiastical service in the pursuit of higher social stations, the family only accepted the king’s offer of the bishop’s position after they understood the king would not provide them with what they truly desired—new seigniorial titles. See Nader, Mendoza Family in the Spanish Renaissance, 49–51.

[vii] RAH, Colección Salazar y Castro, tomo C–20, fol. 212v.

[viii] RAH, Colección Salazar y Castro, tomo C–20, fol. 212v.

Explore the Three-Dimensional Dioramas

Land Ownership & Leasing

Here, in Plasencia Spain, Archdeacon Carvajal has opted to offer land he acquired to his lower level family members. Read more

Taxation

November 1425, Bishop Santa María appointed Gonzalo Garcia to gomake a delivery to Juan II. Read more

From Knight to Clergy

Gonzalo Garcia’s transition from knighthood to the church was one that completely reshaped the way the carvajals operated. Read more

3D Printing and Creation Process

To learn more about the process for creating these virtual three-dimensional dioramas, and to view the final 3D printed dioramas, please visit the documentation page.

Sources

Martínez-Dávila, Roger Louis. Creating conversos: the Carvajal-Santa María family in early modern Spain. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2018. Herrin, Judith Eleanor. “HIstory of Europe - Landlords and Peasants” Encyclopedia Britannica. Updated November 26, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-Europe/Landlords-and-peasants Accessed 28 October 2021. Norris, Michael. “Feudalism and Knights in Medieval Europe.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/feud/hd_feud.htm Accessed 1 October 2021. “Winemaking During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.” The inquisitive vintner [ + His Daughter]. 2018. Winemaking During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. https://theinquisitivevintner.wordpress.com/2018/04/01/winemaking-during-the-middle-ages-and-the-renaissance/ Accessed 4 November 2021. Black, Winston E. "The Medieval Archdeacon in Canon Law, with a Case Study of the Diocese of Lincoln." Order No. NR39883, University of Toronto (Canada), 2008. “Ecclesiastical Property Ownership in the Middle Ages.” Unam Sanctam Catholicam. 2021. http://www.unamsanctamcatholicam.com/history/historical-apologetics/79-history/501-church-owned-land-middle-ages.html Accessed 8 November 2021.