Welcome to Virtual Plasencia 2.0. It explores Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Life from (1200-1500 CE)

Experience the city via Luis de Toro’s sixteenth-century etching of the city of Plasencia.

The City of Plasencia, Spain

Plasencia was at the core of important developments in the late medieval and early modern world. For example, the leaders from this city secured King Ferdinand and Queen Isabel their most important title, “The Catholic Monarchs”, from the papacy. These same leaders were also responsible for securing the papal bulls that gave the Americas to Spain, for negotiating the marriage of England’s Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon and for challenging Pope Julius II for the papacy in 1512 (with the assistance of the French and Machiavelli). In addition, leaders from Plasencia served as the first royal administrators of the Consejo de las Americas (the official Spanish American government) and prepared the first revised collection of official state histories for the new united kingdoms that made up Spain.

In short, the community of Plasencia and their influential citizens, had a broad impact on the events that helped shape Spain and Europe. However, these momentous events did not self-generate or form in a vacuum, rather, they were the byproduct of the unusual conditions and relationships that began in the frontier-city of Plasencia. These unique influences included:

Cooperation, conflict, and disruption were all a part of daily life. The city and the surrounding area were a lively inter-religious community with sizeable Jewish and Muslim populations residing under Castilian Catholic rule. Perhaps it might seem unexpected, but over time these communities formed unusual interfaith, political, and economic alliances.

Rebuilding and visualizing these alliances offers a compelling and novel way to analyze this period of Spanish history.

Competing and overlapping structures of political authority and governance (including, royal, municipal, seigniorial and ecclesiastical jurisdictions) created a dynamic environment of competition and cooperation where various and influential interactions emerged.

Diversified natural resources (from vineyards to mining) shaped economic trade and generated new group identities that often challenged traditional Catholic, Jewish, and Muslim roles in society.

The community’s institutions and leaders were important ecclesiastical and administrative innovators who influenced the development of the Roman Catholic Church, the Spanish royal government in Spain and in the Americas, inevitably forging global networks during the 16th through 17th centuries.

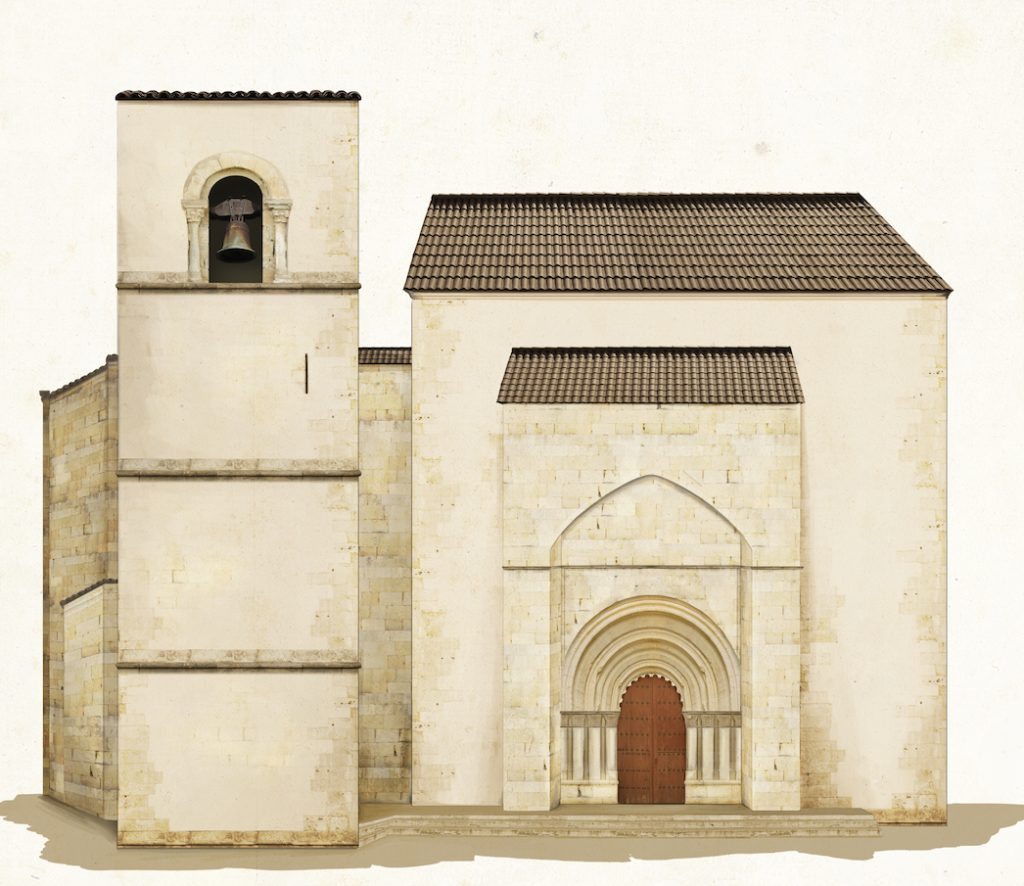

The Cathedral of Plasencia

The first bishop of Plasencia, who led the city through the period of Christian and Muslim reconquests of the region (1189– 1212), is only known as “Don Bricio.” He initiated the construction of the first cathedral in the city (now known as the Old Cathedral), but other than this detail, there is no record of his family or his church deacons and other officials.

To learn more about the Spanish Inquisition in Plasencia, and the torture methods used, click here.

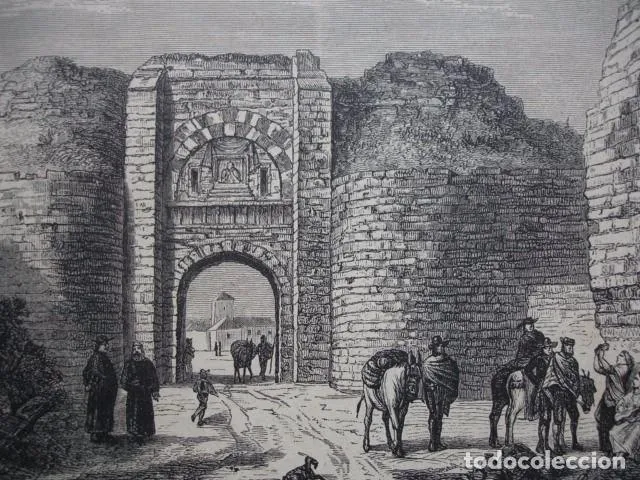

The Gate of Toledo

The city gate led to the important city of Trujillo, The walled city relied on five gates both to facilitate the flow of people and goods and to deny access to enemies. Four of the city’s gates (puertas), the Puerta de Talavera, Puerta de Trujillo, Puerta de Coria, and Puerta de Berrozana, led to nearby villages and territories. The fifth, the Puerta del Sol, was oriented to the sunrise. Flowing inward from these exterior points, like spokes on a wheel, were several major streets that led to the Plaza Mayor.

Entering the city from the south, one traveled through the Puerta de Trujillo and on to Calle de Trujillo. Along this road, which led directly to the Plaza Mayor, were houses with corrals and stables. The church also owned many of these, often leasing them to church officials and local residents.64 The street also served as a boundary between the Jewish quarter to the north and the Christian sector closest to the cathedral.

The Synagogue of Plasencia

As long as there was a city in this region, there was a Jewish community. In 1493, this section of town lost its center of Jewish life when the Catholic monarchs forced the Jewish community to “hand over the keys of the synagogue” to local Christian leaders.

The Gate of Coria

This is the gate that leads to the city of Coria, near the border with Portugal.

North of the Calle de Trujillo was the Puerta de Coria, which led to the Jewish quarter filled with Christian nobles. The two roads connecting this western gate to the Plaza Mayor, Calle de Coria and Calle de la Rua/Zapatería, ran through the center of the Jewish quarter. In actuality, by the 1300s this section of the town was not exclusively Jewish. Both Jews and Christians lived and owned property here. The Church of Saint Nicholas (Iglesia de San Nicolás) and the Jewish synagogue were also located on this road. Established in 1326, the church was built on the foundation of an old Roman temple.

To learn more about wine smuggling in Plasencia, click here.

The City’s Plaza Mayor

The Plaza Mayor was both the center of civic life and the location of surrounding residences for Jews, Christians, and Muslims. In the ideal Spanish Christian world, this should have been an exclusively Christian zone. When the city council (consejo) announced critical decisions, like that affecting the local taxation of wine, the city crier (pregonero) made these pronouncements in the Plaza Mayor.

Although the city had a Jewish quarter (judería) and a Muslim quarter (morería), Muslims and Jews also lived in other parts of Plasencia. Many religious minorities chose to live in these loosely defined zones. The city was an open community where Jews, Christians, and Muslims resided alongside one another. The large judería dominated the western portion of the city and could be entered via the Puerta de Coria or the Puerta de Trujillo. Under Christian rule, the Muslim population contracted and found itself settled in the eastern part of the city, between the Puerta de Talavera and the Puerta del Sol.

The Gate of Talavera

From the southeast, one entered through the Puerta de Talavera and passed along Calle de Talavera to the center of the city. On this lane was one of the oldest parishes the Church of Saint Steven (Iglesia de San Esteban), which the clergy had reportedly founded as early as 1254.

This city gate no longer exists.

Image Source: GRABADO DE LA ILUSTRACION IBERICA AÑO 1888.

The Gate of the Sun

Entering the city from the east would take one through the Puerta de Sol and westward along Calle de Sol to the central plaza. The eastern section of the city was designated the Muslim quarter (aljama). Yet this was not a religiously one-dimensional space. On this primary thoroughfare, the cathedral owned numerous houses, many of which were close to the Plaza Mayor. In the vicinity of these homes and close to the Puerta de Sol was the Islamic mosque, which during the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century was converted to the Church of Saint Peter (Iglesia de San Pedro). According to one of the principal historians of the city, D. Jose Benavides Checa, the first reference to Christian artwork and a chapel in the former mosque was not recorded until 1562. Thus it appears the mosque remained a Muslim house of worship at least into the late 1400.

The Mosque of Plasencia / Church of St. Peter

The city’s Islamic mosque, which during the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century was converted to the Church of Saint Peter (Iglesia de San Pedro). According to one of the principal historians of the city, D. Jose Benavides Checa, the first reference to Christian artwork and a chapel in the former mosque was not recorded until 1562. Thus it appears the mosque remained a Muslim house of worship at least into the late 1400.

The Church of St. Steven

The Church of Saint Steven (Iglesia de San Esteban) was reportedly founded as early as 1254.

The Castle of Plasencia

The castle of Plasencia. It was destroyed in during the 20th century to expand the city beyond its original walls.

In November of 1425, Bishop Santa Maria appointed Gonzalo Garcia de Carvajal to make a deliver to King Juan II. When the King visited Plasencia he would have taken up residence in the castle. To learn more about this moment in Carvajal’s life and the power dynamic between the Church and the King, click here.

The Church of St. Nicholas

The earliest accounts of the church are found in royal documents. An 1188 royal donation of property from King Alfonso VIII to Pedro Tajabor, archpriest of Ávila and archdeacon of Plasencia, just one year before its reconstitution, reveals the limited resources of the city. As Tajabor described it, “I encountered a dam in Plasencia, on the Jerete River, situated close to the city’s gate of Santa María. The city’s dam was intact in its totality and it had a watermill and aqueducts constructed there. . . . [Y]ou, [King Alfonso VIII], also made a donation of an ancient church in the city. . . . We found the undisturbed church where the ancient city was first established.”

Formally established in 1326, the church was built on the foundation of an old Roman temple. The Church of Saint Nicholas was an important venue because interfaith disputes were resolved at its front doors. In “extraordinary circumstances,” a Jewish judge and a Christian judge heard and adjudicated cases on the church’s steps that involved conflicts between individuals of these different faiths. The synagogue of Plasencia, the Jewish confraternity (cofradía de los judíos), and a large block of enclosed Jewish residences (Apartamiento de La Mota) sat across from the church. Although this was a predominantly Jewish section of Plasencia, Christian clans such as the Carvajal and the Estúñiga had constructed homes there by the 1400s.

The ancestral Carvajal family houses.

In 1252, the Old Christian Carvajal clan first appears in the local historical record when the knight Diego Gonzalez de Carvajal founded the Monasterio de San Marcos. Local chronicles note that Diego and his father resided in Plasencia and were in the service of King Fernando III. The two men participated in the king’s military campaigns against the Iberian Muslims and reportedly attended to the king’s mother, Doña Berenguela, as her stewards (mayordomos). After the reconquest of Sevilla (1248), Diego retired to Plasencia; the family continued to reside there as a minor noble clan of modest means up through the fourteenth century. Spanish nobility genealogies maintain that the Carvajal family of Plasencia was descended from the line of King Bermudo II of León (r. 982– 99) and through these noble origins entered knightly service.

Gonzalo Garcia de Carvajal decided to take his life and his destiny into his own hands, transitioning himself from a knight to a member of the clergy. This completely changed his family’s role and identity in Plasencia. To learn more about this story, click here to view a three-dimensional diorama capturing this important moment.

Diagram of the “Old” Cathedral Floorplan

KEY POINTS OF INTEREST 1. Main altar 2. Altar of the Crucifixion 3. Altar of Our Lady of Mercy 4. Sacristy 5. Door of Mercy 6. Chapel of Saint Vincent 7. Chapel of Holy Mary “The Fair” 8. Choir 9. Doors to the Cloister 10. Chapel of Saint Catherine 11. Altar of the Choir 12. Chapel of the Doctors 13. Main door 14. Cloister 15. Plaza of the Oranges and Fountain of Juan de Carvajal 16. Altar of Our Lady of the Cloister 17. Chapel of Saint Paul and the Cathedral Chapter Hall 18. Bell Tower

Residence of Gonzalo Garcia de Carvajal (circa 1430s)

Included in this area were homes owned by Garci López and other houses leased by Archdeacon Alfonso García de Santa María, all of which were across the street from the cathedral and on Calle de Iglesia. The bonds between the Carvajal and Santa María families were so secure that, during the 1430s, the elderly archdeacon Gonzalo García de Carvajal resided in a home with his family member, Alfonso García de Santa María, and Alfonso’s wife and children.

Residence of Amat Moro Bexarano (approximate location)

During the 1430s, Amat Moro Bexarano, a Muslim, lived on Calle de Santa María, alongside Canon Fernán Martínez and the Christian Luis Alonso de Toledo.

Residence of Çag Escapa, on Calle de Zapatería

Çag Escapa a Jewish chainmail maker, lived in this approximate area during the early 1440s. He leased the property for 120 maravedís (silver pieces) and 2 pair of chickens.

Vineyard

This area of church owned land is an example of the type of land that Archdeacon Carvajal might have offered to his family members to create a vineyard. By doing this, Carvajal was able to collect taxes on the land while also giving his family the opportunity to build on their own personal wealth. To read more about this story, and to learn about the significance of land ownership and leasing, click here.

Source :Biblioteca de la Universidad de Salamanca (BUS), MS 2.650. Descripción de la Ciudad y Obispado de Plasencia por Luis de Toro, fols. 25– 26

Experience the city through digital narratives and 3D models

During fall 2021, UCCS history students in HIST 3100: Digital History and Prof. Martinez-Davila developed digital narratives and 3D models and prints to evaluate and present the history of the medieval community of Plasencia, Spain. This website presents three elements of this history as “Virtual Plasencia”.

The three projects include:

Three-dimensional models and virtual models of Gonzal Garcia de Carvajal’s life.

Digital Narration 1: Wine Smuggling in Plasencia, Spain

Digital Narration 2: At What Cost? An Introduction Into Four Spanish Inquisition Torture Methods